Green Nazis

Hitler’s Mein Kampf has become something of a bestseller recently in Turkey, a disturbing fact noted by Doug Saunders in Saturday’s Globe and Mail. Fascism is generally considered a phenomenon of the extreme right, yet conservatives nowadays often claim it is really a left-wing ideology, invariably pointing out that Nazism is short for Nationalsozialismus (National Socialism). This is disingenuous. “Socialism” meant something quite different to the Nazis than it did to the left. Long before he came to power, Hitler developed a fanatical hatred for two categories of people: Jews and Marxists, both of whom he regarded an inimical to his idea of a strong, racially united Germany. In his eyes, Marxists (who included not only Communists but Social Democrats) were traitors to Germany, who had sold out the country at the end of World War One. But his hatred for Marxism arose from more than Germany’s defeat. Left-wing socialism is based on the ideals of egalitarianism and internationalism, while fascism is based on hierarchy and nationalism. In a 1926 speech, Joseph Goebbels put the matter succinctly: “The Socialism that we want has nothing at all to do with the international-Marxist-Jewish levelling out process. We want Socialism as the doctrine of the community. We want Socialism as the ancient German idea of destiny.” For his part, Mussolini explicitly emphasized fascism’s rejection of the equality espoused by Marxism, and of liberalism’s belief in individual rights.

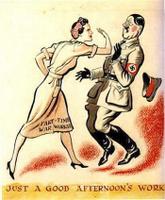

Hitler’s Mein Kampf has become something of a bestseller recently in Turkey, a disturbing fact noted by Doug Saunders in Saturday’s Globe and Mail. Fascism is generally considered a phenomenon of the extreme right, yet conservatives nowadays often claim it is really a left-wing ideology, invariably pointing out that Nazism is short for Nationalsozialismus (National Socialism). This is disingenuous. “Socialism” meant something quite different to the Nazis than it did to the left. Long before he came to power, Hitler developed a fanatical hatred for two categories of people: Jews and Marxists, both of whom he regarded an inimical to his idea of a strong, racially united Germany. In his eyes, Marxists (who included not only Communists but Social Democrats) were traitors to Germany, who had sold out the country at the end of World War One. But his hatred for Marxism arose from more than Germany’s defeat. Left-wing socialism is based on the ideals of egalitarianism and internationalism, while fascism is based on hierarchy and nationalism. In a 1926 speech, Joseph Goebbels put the matter succinctly: “The Socialism that we want has nothing at all to do with the international-Marxist-Jewish levelling out process. We want Socialism as the doctrine of the community. We want Socialism as the ancient German idea of destiny.” For his part, Mussolini explicitly emphasized fascism’s rejection of the equality espoused by Marxism, and of liberalism’s belief in individual rights.On the psychological appeal of fascism, I recommend Bernardo Bertolucci’s film The Conformist, and also White Lies, with Sarah Polley. Both vividly portray how fascism can hook individuals by providing them with convenient scapegoats for the problems in their lives, and with a sense – one they have been missing – of belonging to a supportive community of like-minded persons. But a significant part of the appeal of Nazism, I believe, lay in its call for a return to nature; this was the context of its notion of healthy communities as a remedy for the ills brought on by modern civilization. Not many people today are aware that there was a large ecological component to Nazi ideology – or that the very word “ecology” was coined by an influential nineteenth-century biologist and proto-fascist, Ernst Haeckel. Haeckel and his followers expounded a kind of social Darwinism, claiming that human beings could not transcend the harsh biological laws of the struggle for existence. Later, Hitler said, “Just as the conception of the nation was a revolutionary change for the purely dynastic feudal states, and just as it introduced a biological conception, that of the people, so our own revolution is a further step in the rejection of the historic order and the recognition of purely biological values.” Both German and Italian fascists vehemently rejected the Enlightenment ideal of historical progress that characterizes liberalism and left-wing socialism.

To say that Nazism had an ecological component – and not only in theory: for example, Walther Darré, the Nazi Minister of Food and Agriculture, was an avid exponent of organic farming – is of course not to say that ecologists or the modern environmental movement are fascist. The Nazis identified with nature, but with a particular, dog-eat-dog version of nature. And while German fascism was not a left-wing movement, neither did its demand for a radical remaking of society comport with traditional conservatism either. Fascism does not fit easily into a one-dimensional left/right political spectrum. Unfortunately, it is a monster that refuses to stay dead.